Though the percent of physicians’ time spent on clinical practice may be a consideration in premium setting, the role of clinical volume in MPL risk has received much less attention than has physician specialty.

A recent study in The Journal of Patient Safety explored this relationship, using data on the volume of clinical activity of individual physicians linked with their malpractice claims experience. 3 The study examined how clinical volume affected two different MPL outcomes: annual malpractice claims and claims per patient encounter.

This article explores this relationship, focusing on the ways that MPL carriers and providers can leverage clinical volume data as a factor in predicting risk and setting MPL premiums.

Implications of Clinical Volume for MPL Risk

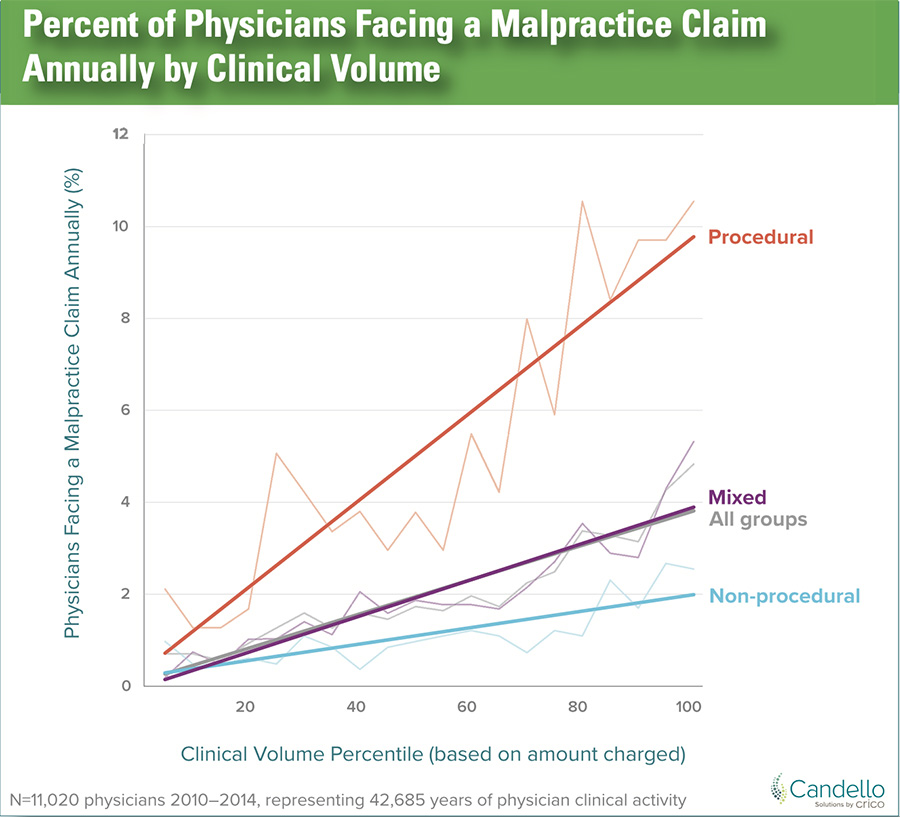

As physicians’ clinical volume—measured by amount charged— increased, their annual risk of facing a malpractice claim also increased, in a roughly linear fashion.

The effect of clinical volume on MPL risk was pronounced. The highest volume physicians had a predicted 14.4-fold higher annual risk of being named in a malpractice claim, compared to the lowest volume physicians.

The effect of clinical volume on the risk of a malpractice claim per patient encounter was also analyzed. This is the metric most likely to matter to patients, who will be concerned with the risk of an adverse event for their individual encounters. The per-encounter risk of a malpractice claim was higher for lower volume physicians.

A threshold effect was apparent: for physicians below the lowest quartile of clinical volume, the per-encounter risk of a malpractice claim went up as clinical volume decreased. For physicians in the highest three quartiles of clinical volume, whose clinical volume was above this threshold, the per-encounter malpractice risk was stable as clinical volume increased.

This relationship between clinical volume and malpractice risk was observed for both physicians who perform procedures and those who do not. Similar relationships between clinical volume and patient safety outcomes have been demonstrated for surgeries performed by individual physicians, and for medical diagnoses at the hospital level. 4,5,6 This similarity in the volume-outcome relationship for MPL claims and patient safety metrics supports the use of MPL claims as a proxy for adverse patient safety events more broadly.

Using Clinical Volume Data Effectively

The utility of clinical volume data for malpractice insurers depends on the type and quality of data collected. The percentage of time spent on clinical activities, especially when self-reported by the clinician, is inexact because different physicians may have different notions of what constitutes a 100% clinical schedule. There are more exact measurements of clinical volume, including:

- The number of patient encounters, which tallies the number of patients that a physician sees.

- Relative value units (RVUs), which are designed to quantify the intensity of the clinical services provided to each patient, and so capture the difference between an annual physical exam and a major surgery.

In fee-for-service environments, RVUs may serve as the basis for physician payment. 7 Both patient encounters and RVUs are generated from billing data and so should be available for attending physicians. However, they are not available for physicians who do not directly bill, such as resident physicians.

There are some important caveats in interpreting this clinical volume data. RVUs tend to be substantially higher for procedural services, compared to non-procedural visits. That means that RVU comparisons between a procedural specialty, such as orthopedic surgery, and a non-procedural specialty, such as general internal medicine, should be approached with caution. Because of this discrepancy, it is prudent to perform RVU comparisons among physicians in the same specialty, or in related specialties. Also, the patient encounters and RVUs of physician assistants and resident physicians may be attributed to the supervising attending physicians, and so such supervising physicians may have high numbers of patient encounters and RVUs.

Clinical Volume Use Case

For medical professional liability insurers, a key use case for clinical volume data is to assist in understanding MPL trends. When the clinical volume of a patient care unit—such as a primary care practice or emergency department—increases, a rise in the annual number of MPL claims is to be expected. Collecting clinical volume data over time can allow the insurer to forecast the anticipated claims experience more accurately.

In the event of a spike in MPL claims for a clinical department, the rate of claims can be expressed as the rate of claims per RVU over time. This will facilitate an understanding of the extent to which that increase in claims is driven by an increase in clinical volume. For example, the patient safety implications of an increase in MPL claims at an emergency department that has expanded its capacity, resulting in a doubling of the patient volume, is very different from that of an emergency department treating a stable number of patients. This difference in patient safety implications may be especially important for captive MPL insurers as they partner with their insureds to identify and rectify patient safety vulnerabilities.

The increased per-encounter risk of MPL claims for low-volume physicians has notable patient safety implications. Encouraging a recommended minimum number of procedures that surgeons should perform to maintain proficiency is an issue that has been discussed in the surgical literature. 8,9 MPL insurers would benefit from considering the nuanced relationship between MPL risk and clinical volume if they are going to offer reduced premiums for clinicians with lower clinical volume.

An option for MPL insurers to support physicians with declining clinical volume, while also promoting patient safety, is to design products for senior surgeons who no longer want to operate but who aren’t ready to retire. In such cases, a role that involves mentoring more junior surgeons and participating in conferences may be appealing. Surgical leaders are a proponent of this approach. In a survey of surgical chairs, the strategy for transitioning senior surgeons to non-operative roles that had the highest level of support was “transition[ing] to teaching or other academic roles. 103 ”Offering MPL insurance designed for this situation can mitigate a financial barrier to the creation of such non-operative positions for senior surgeons.

Listen to the Volume Signals

Neglecting to consider clinical volume can create a blind spot for MPL insurers. The thoughtful use of clinical volume data, which are already collected by providers for billing purposes, can assist MPL carriers in anticipating future claims volume and understanding the claims trends they observe.

Especially when there is an increase in claims, physicians and clinical leadership understandably want to know the “why” behind the unfavorable trend. Having reliable clinical volume data can help unravel the factors driving an increase in MPL claims and help to mitigate risk in the organization.

References

1 Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636.

2 Schaffer AC, Jena AB, Seabury SA, Singh H, Chalasani V, Kachalia A. Rates and characteristics of paid malpractice claims among U.S. physicians by specialty, 1992-2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):710-718.

3 Schaffer AC, Babayan A, Yu-Moe CW, Sato L, Einbinder JS. The effect of clinical volume on annual and per-patient encounter medical malpractice claims risk. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(8):e995-e1000.

4 Ross JS, Normand S-LT, Wang Y, et al. Hospital volume and 30-day mortality for three common medical conditions. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1110-1118.

5 Holt PJ, Poloniecki JD, Khalid U, Hinchliffe RJ, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Effect of endovascular aneurysm repair on the volume-outcome relationship in aneurysm repair. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(6):624-632.

6 Landon BE, O'Malley AJ, Giles K, Cotterill P, Schermerhorn ML. Volume-outcome relationships and abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Circulation. 2010;122(13): 1290-1297.

7 Stecker EC, Schroeder SA. Adding value to relative-value units. N Engl J Med. 2013 Dec 5;369(23):2176-9.

8 Adam MA, Thomas S, Youngwirth L, et al. Is there a minimum number of thyroidectomies a surgeon should perform to optimize patient outcomes? Ann Surg. 2017;265(2):402-407.

9 Franchi E, Donadon M, Torzilli G. Effects of volume on outcome in hepatobiliary surgery: A review with guidelines proposal. Glob Health Med. 2020;2(5):292-297.

10 Rosengart TK, Doherty G, Higgins R, Kibbe MR, Mosenthal AC. Transition planning for the senior surgeon: Guidance and recommendations from the society of surgical chairs. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(7):647-653